“Does ivy hurt my trees?” is a question homeowners regularly ask. The answer is complicated, so read on to learn whether or not you should tear those tentacles off your tree’s trunk.

Isn’t ivy a common garden plant?

First, let’s be clear about what we mean by “ivy.” We’re talking about English Ivy (Hedera helix), not Boston Ivy (that’s a completely different species of vine, Parthenocissus tricuspidata).

You’ll find English Ivy in plenty of gardens and plant nurseries throughout New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and surrounding states.

Ivy has long been used as a groundcover and is valued for its consistent appearance and ability to cover large areas. If kept under control and confined to its intended area, ivy doesn’t pose a problem for trees. But when an ivy stem reaches a tree’s trunk, it attaches itself to the tree’s bark and heads upwards into the tree’s crown. This is where problems can start.

How does ivy climb trees?

Ivy uses two important mechanisms to overtake surfaces, including trees: attachment points and sunlight-oriented growth.

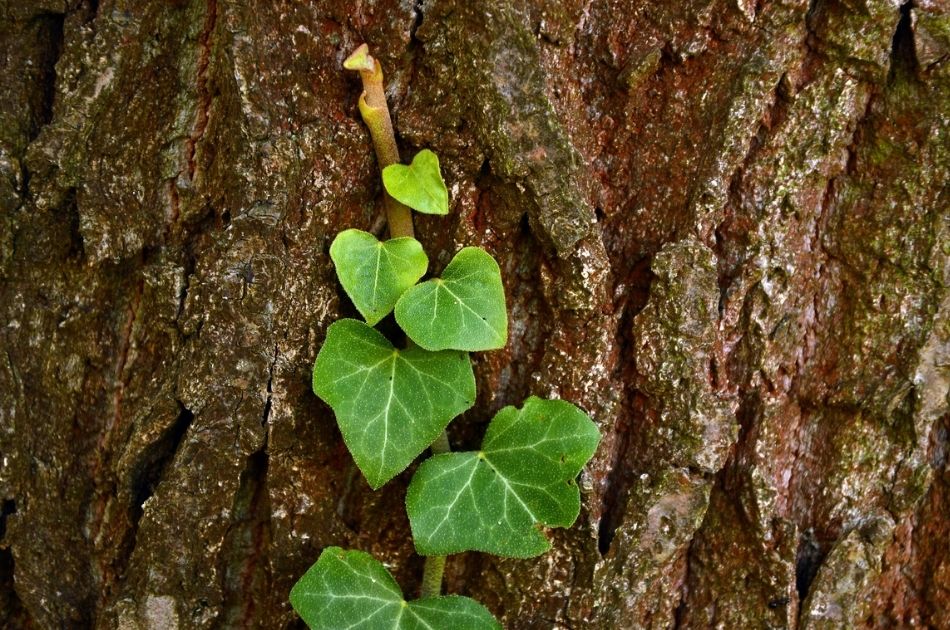

Once the stems of ivy find a surface to attach to, the plant modifies its leaf-node root hairs to become attachment points. The plant increases the surface area of these modified root hairs and excretes a kind of “glue” from the root hair to bond to the surface it’s climbing. If you’ve ever tried to pull ivy off a wall, fence, or other surface, you know how strong that “glue” is!

Once the ivy’s stems are secured, they grow upward and outward in search of sunlight.

Why does ivy climb up trees?

A tree’s bark offers an ideal surface for ivy roots to attach to. Even smooth bark still has tiny fissures for root hairs to reach into and grab hold of. Trees with rough, platy bark offer woody or corky surfaces fissured with deep channels that ivy can easily cling to.

And all tree trunks are growing upward toward sunlight, where ivy wants to be. By growing at the top of a tree, ivy gets far better exposure to sunlight than it does at the base of the tree.

How does ivy harm a tree?

According to The American Ivy Association, ivy growing only on a tree’s trunk isn’t interrupting that tree’s photosynthesis. Plus, the waterproof nature of bark means ivy isn’t extracting water and nutrients from the tree. So, as long as there’s only a little bit of ivy and it’s only on the trunk, it’s not likely to directly hurt the tree.

However, ivy climbing up a tree grows quickly and it isn’t likely to stop growing. And when ivy smothers a tree’s trunk, the problems begin.

- Ivy will siphon resources (water and nutrients) from the surrounding soil to support its own growth, taking those resources away from your trees.

- Ivy covering your tree trunk means that a tree’s trunk flare and anchoring roots can’t be easily evaluated for safety by an arborist.

- If there are any structural defects or damage that could become a hazard, they’ll be difficult to see when covered by ivy.

- A thick coating of ivy can hold plant debris and fungal spores that can compromise the tree’s health.

- Heavy growth of ivy can provide shelter and hiding places for rodents and other pests.

- Ivy uses your tree’s trunk and branch structure as a scaffold to climb, eventually covering many (or even all) of the branches. Its weight and spread can create unbalanced branches that are more likely to break, especially during storms.

- In the crown of a tree, ivy can overtake the tree’s own foliage, blocking the sunlight that foliage needs to photosynthesize and make energy stores.

Over time, these growth habits will weaken a tree by compromising the tree’s ability to take up water and nutrients from below and to convert sunlight into energy from above. And a weakened tree is susceptible to both insect pests and diseases.

Should I remove ivy from my trees?

Whether or not you should remove ivy from your trees depends on your situation. The severity of ivy’s damage to trees is dependent on how and where it’s growing, and how much ivy is in your tree’s crown. But, eventually, you will need to get rid of the ivy in your tree.

However, do not pull ivy off your tree!

The real damage to a tree’s bark comes when homeowners try to pull off the ivy stems that are glued to the bark.

Pulling or yanking off ivy stems will inevitably remove chunks of bark; ivy roots are so strongly attached to tree bark that they take the bark with them when pulled off. Tearing off bark creates openings in the cork, or protective exterior bark layer that expose the vulnerable, interior tissue of the tree to pests and disease.

If I can’t pull it off, how should I remove ivy from my tree?

Instead of pulling down ivy, sever all of the ivy stems growing up the tree at the tree’s base. You’ll be cutting a band of ivy stems around the trunk to separate them from their “parent” ivy plants rooted in the ground.

Once severed, the ivy stems on the tree will die. Let them wither and allow the stems and anchoring roots to decay. You can leave the dead ivy attached to the tree; it won’t harm the trunk and the dead leaves will eventually fall.

How else can I control ivy?

There are a couple of methods to control or eliminate ivy.

Manually Remove Ivy Plants

- After severing the ivy stems on your tree’s trunk, remove ivy that’s growing in the ground around your trees. If you don’t do this, the stems will form new growth where you cut them and ivy will start climbing your tree again.

- The most effective way to get rid of ivy is to dig out its roots. It can be tough going so try watering the area beforehand to soften the soil (or wait until after a rainfall). Be sure you don’t miss any roots – ivy plants put out roots at each leaf node wherever ivy stems touch the ground.

- Be careful when removing ivy roots within the dripline of a tree; the tree’s delicate feeder root system is just below the soil’s surface and you don’t want to damage it.

Use Sprays to Kill Ivy

Spraying should only be done on ivy plants growing in the ground. Never spray ivy growing on a tree.

Spraying is easier than digging but can be ineffective if not done thoroughly. The surface of ivy leaves has a protective coating that resists water and herbicides, making it difficult to affect the leaf tissue beneath the coating.

If you spray using herbicides, choose a calm day to minimize damage to other plants from spray drift. Apply it as close as possible to the ivy’s leaves and cut stem ends.

You can also make a DIY vinegar spray to kill the leaves, but be aware of the amount of salt that many recipes call for. Salt may kill the roots of ivy, but the salt added to the soil will damage the roots of whatever else is growing there.

Any tips for preventing ivy from growing back?

No matter the method used, removing ivy is labor-intensive. You’ll have to keep checking the cleared area every few weeks to dig up any new ivy sprouts. Spread mulch or use sheet-mulching (placing a layer of overlapping cardboard beneath the mulch) in a three-foot circle around your tree’s trunk base. This will help to smother any ivy sprouts trying to re-grow, and you’ll get the other benefits that mulch offers.

PRO TIP: Almost any piece of ivy stem left over from removal can sprout roots and begin growing new leaves and stems, so be sure to rake up all ivy debris. When you rake up the debris, dispose of it in your green waste can. Do not put it on your compost pile until it has died (bag it securely while waiting for it to die). While ivy is still alive, there’s a high likelihood it will re-sprout and take over your compost pile!

If ivy is bad, why is it so common?

Lots of plants have been imported from other countries and continents and then sold to homeowners. In the U.S., the first commercial nursery was started in 1737! While many introduced plants beautify our gardens and pose no problems, some can be a major nuisance. Even plant enthusiast Thomas Jefferson imported and grew plants at Monticello that later turned out to be invasive species!

Many plants that scientists consider invasive or dangerous to native ecosystems are legally sold in nurseries. Because the U.S. has a wide range of climate zones, a plant considered invasive in one location may not be a threat in other locations where temperatures or moisture may control its growth. Until invasive plants are comprehensively banned from the nursery trade, they will be available for sale.

The USDA’s National Invasive Species Information Center (NISIC) has federal and local information about invasive species. From there, you can find a comprehensive list of invasive plants and animals that are found in New Jersey. Hedera helix is included on this list of invasive plants for our area.

You can read more about invasive plants and Jersey-Friendly Yard planting ideas here, and you can learn about what’s being done by a non-profit land trust to eradicate invasive plants in the state.

If you’re considering removing ivy, remember that ivy does not provide much for wildlife. Removing ivy and replanting with native plants will be doing our pollinators and wildlife a big favor.

Give Us A Call

If you’re concerned about ivy and the health of your trees, we’ll be happy to come out and evaluate your trees and surrounding landscape. Our Certified Arborists will be able to recommend the best way to deal with any ivy that may be harming your trees.

GET THE LATEST NEWS

Subscribe to the Organic Plant Care Newsletter and get timely and helpful tips and updates monthly.

There's no spam - we promise!